In Escape from New York, Snake Plissken is offered a deal: go into the chaos, retrieve the thing that matters, and maybe—just maybe—you can leave the prison behind. It’s a film about control (from evil folk), systems gone wrong. About how freedom, in the end, isn’t given, Snake takes it back.

That’s exactly where content brands find themselves right now.

We built these towering media cities—Netflix, YouTube, TikTok, Instagram—and slowly handed over the keys to audience data and the algorithms they build.

Let the people chose.

Let the machine sort it.

Let’s give them what they want, when they want it, in the format they already prefer.

All of it, eveywhere

And it worked. Until it didn’t.

My next three posts are about the challenges facing the video content world. This is the first, Escape from the Algorithm. It will be followed with:

Lord of the Punk; how recession and boredom go hand in hand, and this will lead us back into the era of punk

Wuthering Sports; what would happen if Emily Brontë wrote an anime sports story

The Illusion of Choice

In 2006, psychologist Barry Schwartz popularised the term the paradox of choice. The more options we have, he argued, the more paralysed, and ultimately dissatisfied, we become. Today's audiences face a never-ending scroll of “what do you want to watch next?”

Which sounds empowering but often leads to disengagement, or at the very least more fleeting attention.

“Learning to choose is hard. Learning to choose well is harder. And learning to choose well in a world of unlimited possibilities is harder still, perhaps too hard.”

Barry Schwartz, The Paradox of Choice: Why More Is Less

Now take that psychological fatigue and hand it to creators. Creators who are no longer curating stories, but reacting to what’s trending. Who are told to “listen to the data” (NB: data is our friend sometimes, thats me) instead of lead with vision. Who are rewarded for sameness, not originality.

This isn't just about personalisation. It's about abdication of taste, of creativity, of the kind of editorial confidence that once built channels with fans.

And with AI rapidly growing, there is a risk this becomes worse, or better… or we don’t know that we’re part of it.

We Need Editors Again

The golden era of television wasn’t algorithmically generated. It was curated. Commissioning editors, showrunners, and brand managers built long arcs, trusted their instincts, and sometimes—importantly—challenged the audience.

Humans are cognitive misers, as psychologist Susan Fiske put it. We conserve mental energy by relying on habits, heuristics, and defaults. That’s why autoplay and recommendation engines work so well—they reduce friction.

But it’s also why they flatten complexity.

"People are limited in their capacity to process information, so they take shortcuts whenever they can."

Susan Fiske, Eugene Higgins Professor, Psychology and Public Affairs at Princeton University,

Real editorial control introduces tension. It suggests, you might not know you want this yet, but you will. That's the power of great editors, commissioners and programmers.

They are still out there, fighting the fight, and we should give them more time.

Disney did it in the 90s, they still do. Adult Swim did it in the early 2000s and are still doing it with socials added, in-fact Turner Broadcasting were the gold standard.

And even more recently, look at how Bluey broke conventions—long, emotionally intelligent arcs in a preschool format. It wasn’t chasing the algorithm. It was being the adult in the room. And it did so across spaces where parent and child sat together.

Case Study: When Brands Lead, Audiences Follow

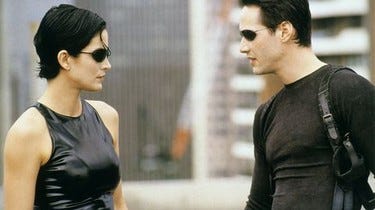

Case 1: Arcane

When Netflix launched Arcane, they didn’t follow their usual binge model. Instead, they released it in three acts—three episodes at a time, over three weeks. That wasn’t just a creative choice. It was a scheduling decision designed to make the show feel like an event.

Each act gave the audience a reason to come back, time to digest, space to speculate. In a platform designed for endless consumption, Arcane paused the feed and created rhythm. That’s what smart, human scheduling can still do—even inside Netflix.

And it fit with an IP that already had a huge fan following in the notoriously highly protective gaming community.

Case 2: Ted Lasso

Apple TV+ could have dropped Ted Lasso all at once. But they didn’t. They chose a weekly rollout, the kind we used to call “appointment viewing.” Not for nostalgia, but because it works. I called it Emotional Scheduling, but actually we do still make appointments as audiences.

It created routine, gave the show breathing room, and made it part of the weekly rhythm for families, sports fans, and anyone who needed something to feel good about. The content earned the fandom, but the structure helped it grow. Scheduling here wasn’t just logistics. It was part of the story.

Audiences don’t need endless choice. They need coherence, voice, and vision.

The Path Back from the Algorithm

Reclaiming editorial control doesn’t mean ignoring data. It means recognising what data can’t do. It can’t forecast emotional resonance. It can’t create surprise. It can’t see around corners.

What it can do is support human judgment—if we let it. Use the data to spot fatigue. To track where a story lands, not how it should start. To validate risk—not avoid it.

This is how brands escape New York. They send someone back in—not to survive the chaos, but to retrieve what matters: the story, the purpose, the arc that holds it all together.

Final Thought: Build Less. Mean More.

In the end, Snake Plissken didn’t try to destroy the system. He just operated outside of it. On his own terms. He didn’t reject structure. He rejected blind obedience.

That’s the mindset we need in content now. Algorithms are useful—they scale, they surface, they optimise. But they don’t know how to shape a moment, build a rhythm, or make something matter.

That’s what human programming still does best. It adds judgement, context, and intention to the feed. It turns output into experience.

So if you want your brand to last, don’t abandon the tools—just stop letting them drive. Pair the algorithm with the editor. Pair the data with the instinct. Let the machine serve the moment, not define it.

Escape the loop. Set the schedule.